A common history, shared by different Nations.

We are tributaries of the same river.

Origins of the Ribbon Skirt: An Introduction

The exact origins of the ribbon skirt are difficult to trace, as all evolution is hard to see in the happening. From our elders, photography and historical records we can piece together a story of several different lines from which the modern Ribbon Skirt has evolved.

I will try to try to help tell on part of the story here. It is important to talk about The Ribbon Skirt from a Métis perspective, without ownership, bias or entitlement, because we are part of the story.

It is important to remember that the Ribbon Skirt of Antiquity is not the same as what we see today. Its uses and traditions, and who wore them has shifted and changed, just as culture is ever-changing and alive.

The Sacred skirts of First Nations women have a lineage and tradition stretching into pre-history. The buckskin dresses of the Plains and ceremonial skirts of all nations, whether made from leather or furs or bark, hold such importance that they are still in use today.

Many Indigenous traditions dictate the use of long skirts in ceremony and Sweatlodge to symbolize our connection to the Earth, so that She would know who was touching her when the wearer made her prayers, and that the fringe of the leather would touch the Medicines as she walked. Some skirts were specific to phases in a woman’s life, from her moon-time to pregnancy. The teachings of the Tipi (Dakota), the Mikiiwaap (Cree), and Enn Lozh (Michif) are directly linked to the to the origins of the teachings of the ceremonial skirts the modern Ribbon Skirt is descended from. These traditions persist, despite the best efforts of those who would hope to diminish traditional ways of life for the First Nations and continue to be that symbol of resilience.

These traditional skirts and their teachings and protocols are the cultural pattern on which the modern Ribbon Skirts are founded. But where does the modern skirt come to us from?

The origins of the Ribbon Skirt belong to not only the First Nations and Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, but to the settlers who first brought their European designs to the prairies. Through generations of intermarriage, trade and cultural cross pollination, we arrive at what we call the Ribbon Skirt today.

In these 1825 illustrations by Rindisbacher, “A Halfcast (Métis) and his Two Wives”, and “In the Tepee” (A Métis Family), the ribbons on the edges of the women’s skirt are clearly visible.

(Rindisbacher was particular interested in capturing Métis life and was diligent in making the distinction between Métis and First Nations in his works, allowing us to rely on his work as reference. This was not often the case with illustrators of the time, and through my research I have found dozens of similar and much more elaborate drawings of obviously Métis women with ribbon skirts. Most of these cannot be attributed to being Métis due to lack of documentation and attention to detail on the part of the illlustrators, and so, cannot be included here though they portray Métis women and families undeniably. )

“In the Teepee”, Rindisbacher, 1825

(Note: For clarification, from this point on I will be referring to Métis, métis, mixed, and country-born in lieu of the more problematic denominations of the day. In the historical context, the use of lower case “métis” refers to individuals of mixed Indigenous and European blood, involved in the fur-trade, and residing in geography generally considered to be significant to the Métis in their nascent stages. It is a racial classification, not necessarily a distinct cultural one in this context. The use of “Métis” (upper case) will refer to members of the nation as it developed into a distinct peoples, and began to claim sovereignty and autonomy in the second half of the 19th century.)

Fabric and Ribbons: 1600- early 1900’s

When the Women of the Land began to intermarry with the Fur-traders of Europe, they became the iconic nomadic Voyageur families that travelled the trade routes of the Northwest and Eastern Canada, developing the beginning of our language, Michif, and a distinctive clothing style. A melting pot of culture and protocol gave birth to new nations and language, but also to exploitation and assimilation, for good or bad.

At the point where these new mixed families began to live in forts and towns as opposed to living with their traditional families in a tribal community setting, there was an expectation of them to don the more conservative dresses and blouses of the day. With access to new trade goods, the materials of their clothing shifted from furs, skins and natural fibers to new ones imported from Europe, including cotton, wool, ribbons, calico and even some silks. The transition seems to have been a relatively fast one, as this shift in available materials started near the end of the 18th century and by the middle of the 19th century, traditional Indigenous women’s dresses were almost unobserved in the urban métis community, though the beaded moccasins, leggings, bags and coats were still in use in towns. Although Métis women had all but completely adopted modern European clothing, the further development of our unique floral beadwork and embroidery flourished in this time under the influence of Nuns and Missionaries attempting to teach marketable skills to otherwise “uneducated” First Nations and métis women, although this was often seen as an export or tourist funded industry of Native Arts rather than a cultural practice.

Ribbons were brought to North America because of trade, but large amounts came came later than other trade goods as extravagant clothing fell out of fashion in Europe due to the cultural shifts caused by the French Cultural Revolution, and the unwanted flashy ribbons and lace trickled down to the colonies. These new trade goods created an entirely different type of economy, encouraging a unique industry in the creation of elaborate ribbon craft and applique in the Great Lakes Region and the Northeast. The two closest regions in contact with new trade goods from Europe and (incidentally saw the highest numbers of early inter-cultural marriages and métis descendants) were able to develop this intricate new art movement early-on. Based on traditional arts developed in quills and parflêche, the geometric patterns made by folding ribbon had a particular and unique allure. (The Mi’kmaq, Fox and Menominee were particularly renowned for their early ribbonwork, and by the early 1800’s, the craft had spread into the Prairies, and Plains, and here we see the development of what will become recognizable as a ribbon skirt.)

From the concise records of imports kept by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) we can see that the amount of ribbon imported for clothing applique at the turn of the 19th century is remarkable. Importations for the “Native-wives” and “Country-born daughters” at Fort Albany between the years of 1800 and 1807 is very well documented. {1} (Incidentally, where my great-great-great-great-great Grandfather John Hodgson was chief factor for HBC at the time, and my own Métis lineage sees its beginning.)

In fact, the HBC records indicate that servants (of the HBC) Thomas Vincent, Robert Goodwin, John Kipling, all Jacob Corrigal purchased a collective 375 yards of ribbon from the company store over a five-year period, all of them had married “Women of the Land” or mixed daughters and granddaughters of the chief factor himself (my ancestor), and had “Country-born” daughters of their own in their households. {2}{3}{4}{5}. Here we see recorded, historical precedence for what would become the Métis, beginning to adorn their clothing with imported ribbons and the sources that provided them.

The ribbons were used as applique in the new sewing techniques taught to First Nations Women and their European-Indigenous Children living near the forts, and included sewing them to the tops of moccasins, the insides of their hoods, the edges of their sleeves, skirts, and leggings.

The use of the Anishinaabe style strap dresses were still in popular use at this time and region, as the métis Daughters and Granddaughters of the Nation still used this basic pattern for a simpler alternative to multi-layered European garments (which were far less practical) and regularly adorned them with ribbons. {6} Traditional First Nations garments and the costume of the fur trapper and Voyageur seem to survive longer in rural environments, but closer to the end of the 19th century, we start to see the abandonment of traditional clothing, beadwork, sashes, Ribbon Skirts and regalia in Métis communities due to mass discrimination and disenfranchisement. The marginalization of Métis people by the Canadian Government after the after the Riel Resistance of 1869–1870 and the North–West Resistance in 1885, forced many of our families into Road Allowances. These were unclaimed, unwanted or un-arable land on the borders of established First Nations Reserves and along roads and crown land, and communities were built without services or infrastructure. While this dispossession spelled poverty and unemployment for many, for others, the only land that they had to call their own meant the road allowances became a haven for cultural preservation, language, traditions and skills. {9}{10}{11}

Many Métis people made the heart wrenching decision to identify themselves with their settler heritage and reject and bury their Indigenous roots for fear of persecution, starvation and this dispossession, and along with that, went many of our traditions and arts handed down from our First Nations Families.

A note on the photographs: While I have been able to collect beautiful photos from many different sources, photographic evidence in historical periods have been difficult to find, owing to several different factors. Given the cultural climate, financial disparity, racism and discrimination, it is not hard to understand why adopting as much of European culture was seen as beneficial to the Métis, especially when it came to clothing. Caught between the traditional world of their First Nations families and the seemingly dominant and “civilized” European roots, many Métis were encouraged to assimilate into non-Indigenous culture, and to conceal their Indigenous roots. It is not a stretch to imagine why there is a lack of photographs of the Métis in their more traditional or ceremonial clothing and instead in their somber, formal Sunday best, given the expense of having photographs taken and the wish to appear modern and wealthy. The racism of the 19th and 20th centuries led to a reluctance of Métis people to identify themselves as such, and in turn to the mislabeling, concealment and denial of beadwork, clothing, photographs and other art that should have been attributed to the Métis.

The First documented use of what is considered to be a true ribbon skirt was worn by a métis Menominee woman

NE-KICK-O-QUA (Sophia Therese Rankin), for her wedding in 1802 in Green Bay, Daughter of the British fur trader David Rankin and French/Odawa/Menominee mother

WE-AW-WE-NING.

A lavish display of the beautiful fabrics, wool cloth and ribbons known to be available to the metis and Menominee at the time due to their trade relationships, is demonstrated in what was sure to be an intentional show of wealth and position in the fur trade. {7}{8}

Wedding dress of NE-KICK-O-QUA circa 1802, Neville Museum Photograph, Green Bay WI. USA.

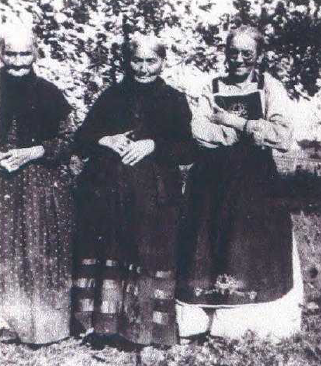

Three Daughters of Norbert Laurence and Marie Parenteau, Marie, Rose and Clarise, wearing ribbon adorned skirts and apron. Date Unknown. Glenbow Archives.

Marguerite Parenteau, Mrs. Xavier Letendre dit Batoche circa 1885, wearing a period typical conservative black dress adorned with ribbons. Glenbow Archives.

"Métis women dressed for centennial celebrations, Elizabeth Metis settlement, Alberta.", 1967, (CU1132812) by Unknown. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

The Ribbon Skirt in Modern Métis History

Join me on the next part of the journey into discovering the Ribbon Skirt in a contemporary context, what it means to Métis culture and stories from knowledge keepers and elders, and how Métis resilience kept culture alive over the decades.